The Painting Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden, The importance of travels for an artist, and reflections on the art of Ike No Taiga

The Painting Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden, The Importance of travels for an artist, and reflections on the art of

Ike No Taiga

Over a thousand years ago in China, there was an artistic movement of “Literati painters.”

These were well-read artists who worked mostly with brush and ink on rice or mulberry paper.

They were more philosophers and visionaries than craftsmen or technicians.

Intentionally, their focus was not to produce pretty or accurate paintings with correct representations of people and nature, but to evoke new feelings and perspectives on life.

They wished to free the human mind from earthly bondage and to uplift the human spirit from the daily grind.

They wanted to show others the unseen world, as seen through their inner eyes.

Much like the European Impressionist painters who conveyed nature through light and feeling, these Chinese literati painters wished to show the hidden, spiritual aspect of the Natural world.

Their ideal was that one could never become a great artist without reading the “Ten thousand volumes” and journeying the “Ten thousand leagues.”

This means that in order to give their audience a new perspective, artists must venture into the world, travel, read, think, dream, and risk everything to stretch their own boundaries.

The term “Ten Thousand” in Chinese and Japanese, refers to the idea of “Many.”

Ten Thousand is an expression similar to when we say: “Oh, I’ve read a million books about....”

Ten Thousand is a term that means “A lot.”

The idea that one can only become a great artist after reading ten thousand volumes and journeying ten thousand leagues, means that one must be filled with knowledge AND experience of the world, in order to paint a true interpretation of the world.

They did not travel to gain a greater reputation for themselves.

They were not interested in fame, nor in seeking fortune.

They believed in being obscure, well read, humble, creative and introspective.

These master painters believed that the first-hand experiences gained in their constant travels were necessary to paint excellent landscapes.

They believed that one could only learn the true nature of people and infiltrate the supernatural nature of Creation, through travel.

They called their landscapes, “True Views Of Mount....,” or True Views Of The ....... River.”

“True” means that they had actually hiked up the mountain and thus were able to bring to the painting the feelings they had while on top of the mountain, or while looking across the mountain pass.

I have always wanted to use my world travels as inspiration for my art.

But somewhere along the way, the love of travel took over, and my time in the studio has shrunk.

Maybe one day it will be different, but for now and for the last two decades, I have felt a strong inner urge to roam the earth.

Travels have turned into pilgrimages, walked in search of enlightenment.

While we were in Kyoto, on a very rainy Sunday, we visited an exhibition by a Japanese painter named Ike no Taiga (1723–1776).

Taiga was inspired by the ancient Chinese literati painters.

Born in Kyoto to a minor official of the silver mint, Taiga lost his father while still a young child.

He began to study calligraphy, and also became a self taught painter.

Taiga started out by making a living selling fans that he had painted in a shop in Kyoto.

He used picture books imported from China as the inspiration for his painted fans.

There were a few reasons I was eager to see the work of Taiga up close.

For one, he taught himself to paint using Chinese painting manuals, the same ones I have collected while traveling in China.

I have used these painting manuals in my art and have learned a lot from them.

I used to return from our trips to China with many instruction books, which I still use as references for my art.

The second reason that I was intrigued to see Taiga’s art is that he painted the 500 Arahats (Enlightened students of the Buddha), which has been my life long dream to paint.

In 2012, the world renowned Japanese artist, Takashi Murakami, completed his own whimsical painting of the 500 Arahats.

Takashi Murakami‘s 500 Arahats, done in acrylics on canvas that is mounted on board, measures 302 x 10,000 cm and is perhaps one of the largest paintings in the world.

It is also a very good painting, depicting the old, humble, wise and enlightened Arahats, in a fun way.

You see, these enlightened Arahats were not superhuman beings.

They were ordinary men and women who knew that we are all unlimited Spirits, and not limited physical beings.

Then, with a commitment to the practice of Truth, they spent their lifetimes living by these principles.

They became humble and luminous, by trial and error.

Their life experiences humbled them, and the Spirit of joy filled their hearts with real optimism.

I am not yet sure how I wish to paint my own Arahats.

All I know for now is that at least half of them will be females.

As to the exact painting methods, whether I will paint them on multiple long scrolls, or on multiple large canvases, I am not yet sure.

I guess I will have to start this long journey and begin painting, looking for clarity as I go along.

To be honest, painting in my studio is the main reason I am eager to go home to Colorado.

Otherwise, I could continue roaming the earth without missing anything, as long as I am with Jules.

There is nothing that I miss at home.

The third reason I was eager to see Taiga, was because he was an inveterate traveler, who used his travels to paint truer views of the landscapes he painted.

Taiga started traveling as a young man, mostly trying to sell the painted fans that he had made.

There were times when, even after traveling long distances, he would return home without having sold a single fan.

This is something I have also experienced.

I did some very successful art shows, but I too traveled at times across America, to do art shows where I did not sell a single painting.

To be honest with you, even now, whenever I have a very disturbed sleep, I have dreamt of being in an art show where nobody likes my art and then going home feeling disheartened and sad.

It is a recurring nightmare for me.

Even though I love the style of Chinese ink brush paintings, I am not interested in using this style in my art.

I keep the use of ink to the background of my paintings, when I work on paper scrolls.

I have used ink in my Shibuya portrait series and in my Divine guardians paintings.

But when I examined Taiga’s style, inspired by the Chinese Masters, I could see some techniques I could apply to my oils and acrylics paintings, which I am going to paint next in my studio.

His use of space in the canvas was very interesting.

Normally, when painting a body of water like a lake or the sea, it is painted horizontally, but Taiga and the Chinese masters painted some of it at an angle, as if the water would slide off the paper into the mountains or the borders of the sky.

Many times, the water and the sky were just left empty, or white, with only a tiny boat to indicate that this was a body of water.

This Chinese-influenced literati style of painting was known in Japan as “Nanga” (“Southern painting”).

Taiga's works are done in a brisk, unfettered style said to exemplify the artist's humble character, and his indifference to fame and fortune.

Many of us could not really tell the differences between some of the old artists who worked in the same Chinese ink painting style.

Some of them are very distinctive, while most of them were influenced by the same painting manuals, and never ventured out of those painting styles to work in a very different way.

Being different and unique was not as important as living a creative life with all the benefits that an artistic and poetic life has to offer to the inner being.

Another reason I was excited to see Taiga’s work is because, like him, I also had a period of time in which I did finger paintings, searching for my own artistic style.

I put aside my brushes and wide collection of pallet knives, and used mostly my (gloved) fingers to shape the oils and acrylic paints I was using.

In the Kyoto Art Museum, the signs said that Taiga used finger painting in his quest for his artistic style.

It said that Taiga often produced paintings using his fingers and fingernails instead of a brush.

The tradition of finger painting (called Shibokuga or Shitōga in Japanese), which came from China, was pioneered in Japan by the literati artist Yanagisawa Kien (1703–1758) as a highly impromptu genre―a sort of improvisational performance art.

In truth, using fingers to manipulate liquid ink greatly restricts the artist’s representational abilities, giving much less freedom of expression than one would have had when painting with a brush.

While not the same as painting with a medium like oils and acrylics, finger paintings are more a form of freedom from exact representation and an expression of the joy of painting, rather than a focus on a perfectly “correct” painting.

I do not know how my phase of finger painting helped shape my own artistic style, but the sign said that for Taiga, it was a milestone in his struggle to establish his own mode of artistic expression.

A part of the exhibition focuses on Taiga's extensive travels throughout Japan as an itinerant painter.

It explained the influence of these wandering days on his artistic development.

The young Taiga learned painting techniques from classic Chinese painting manuals.

Two of these classic manuals are called, “The Painting Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden,” and “Primer On The Eight Varieties of Painting.”

The Painting Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden, in particular, served as both a source for images and also for theories of painting and techniques.

Artists at that time learned to copy the manual’s images of nature and people, in order to learn how to render nature and movement in the classical way.

The book was utilized as a practical guide to painting.

The common belief was that, “An artist must always be aware of the Painting Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden.”

Many artists before Taiga regularly consulted manuals and studied pictorial composition from printed manuals of this sort.

At the time, there were very few opportunities for ordinary artists (“Machi Eshi,” in Japanese) to even see high-quality Chinese paintings.

But some traveled to see great artworks for inspiration.

It is believed that Taiga traveled to see Wang Zhenpeng’s painted scrolls of the Five Hundred Arahats, before painting his own version.

Wang Zhenpeng was a Chinese landscape painter who worked in the imperial court during the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368).

Though he lived 500 years before Taiga, Wang Zhenpeng's scroll of the Five Hundred Arahats was a particularly important artwork, and it had a direct effect on the creation of Taiga's own Five Hundred Arahats.

I have researched the “Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden” (芥子園畫傳, Jieziyuan Huazhuan, also known as Jieziyuan Huapu 芥子園畫譜).

It is said that this printed version of this manual of Chinese painting was compiled during the early Qing Dynasty, from earlier manuals.

Many renowned Chinese painters began their drawing lessons with the manual. It is an important early example of colour printing.

It is easy to see how those artists who studied it, produced early artwork that is very similar in style.

It takes a lifetime to develop your own unique style as an artist.

I am looking forward to spending time in my studio again.

It makes the thought of going home something to look forward to.

I know it will not be easy to paint again.

It takes a lot of practice to get going again.

It is as if my fingers that hold the brush do not obey my mind.

It takes me time to get back into the studio and feel comfortable there.

Once, the famous British artist, Damien Hirst, described his color spot paintings, made by many of his assistants at undisclosed locations.

He said, "They're all a mechanical way to avoid the actual guy in a room, myself, with a blank canvas."

I know how he feels, and I know it will be the same for me....

Myself, lots of time and the blank canvas....

It is a new journey, all by itself...

With love and warm blessings,

Tali

P.S.

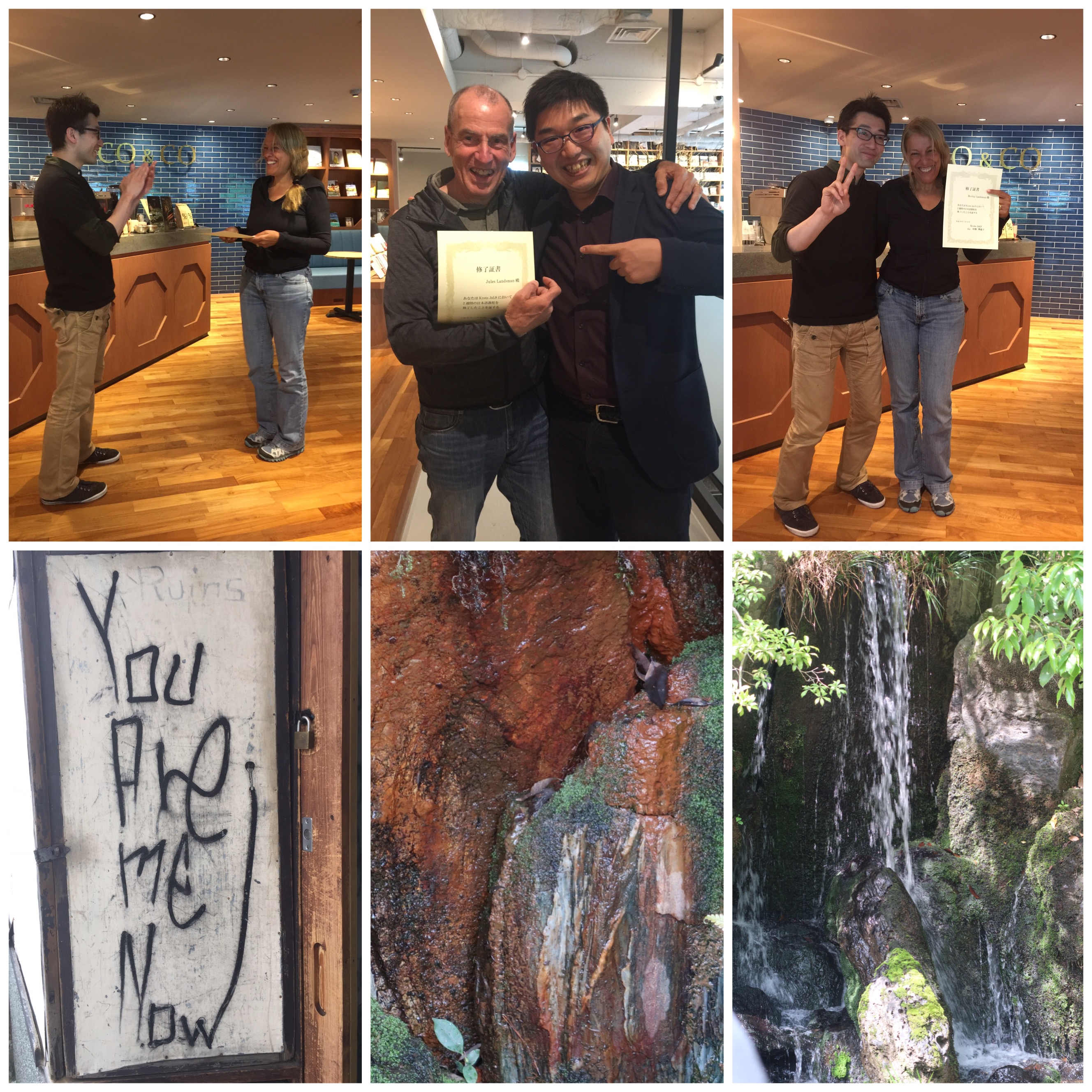

Photography was not allowed in the museum, so I am adding some photos from our time in Kyoto instead.