Huvsgol Lake, Visiting A Reindeer Family, And Why The Camel Always Waits By The Well, Mongolia

The drive to Huvsgol Lake (also spelled Khuvsgul and Khövsgöl) took us through very picturesque landscapes.We could see blue rivers crisscrossing the green pastures, forming the most beautiful abstract shapes.

We would have to cross many of those rivers before we were able to get to our ger camp on the shores of the vast lake.

Some of the wooden bridges crossing these rivers were so badly damaged that we decided to get out of our Land Cruiser and walk across, while Nasaa, our driver, zigzagged his way across the bridge, trying to find the least broken parts of the bridge on which to drive.

By way of comparison, crossing rivers with no bridges at all, where the water came up almost to the height of the windows, was much less scary than crossing those broken bridges.

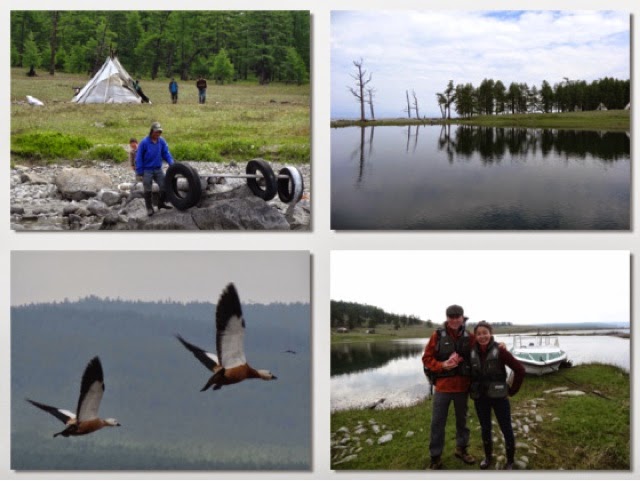

We arrived at Huvsgol Lake by the early evening, just in time to check into our ger and enjoy the beautiful sunset on the lake before dinner.

Huvsgol Lake is surrounded by several mountain ranges, the highest among them the Bürenkhaan Mönkh Saridag (3,492 meters or 11,457 feet).

The lake forms part of the Russian-Mongolian border, and used to be a busy trade route between the two countries.

The surface of the lake freezes over completely in winter.

The icy surface used to be strong enough to carry the weight of heavy trucks during the wintertime, so that transport routes developed on its surface as shortcuts to the normal roads between Russia and Mongolia.

However, this practice has now been discontinued, because it is estimated that 30-40 cars have fallen through the ice and sunk into the lake over the years, their engines leaking oil and petrol and contaminating the lake.

Lake Khövsgöl is one of seventeen ancient lakes around the world that are more than 2 million years old.

In Mongolia, the lake is reputed to be potable without any treatment, although during a long lakeside walk we noticed that many herds of yaks came down to drink at the shore, and the shoreline was filled with manure in some places.

Of course most of the land bordering this vast lake is not inhabited by people.

There are a few tourist ger camps on the southern edge of the lake, and a few communities of indigenous nomads, who live in tipis and are reindeer herders, living in the northern parts year round.

The Lake area is now a National Park with an entrance fee.

It is bigger than Yellowstone and strictly protected as a transition zone between the Central Asian Steppe and the Siberian Taiga.

The locals are no longer allowed to cut any trees for heating during the winter, and commercial fishing is illegal.

Despite Khuvsgul's protected status, illegal fishing is common and you can even buy smoked lake fish in the nearby village of Hatgal.

The lake is so large that the locals refer to it as "Huvsgol Ocean."

This nickname was adopted because of something that actually happened here, hundreds of years ago during the Manchurian occupation.

The Manchu rulers decided to increase their tax revenues by instituting a tax on all of the many lakes around Mongolia.

The local nomads who had so few resources to spare to pay yet another tax, argued with the Manchurians that Huvsgol was not a lake, but an ocean.

The Manchurians, who had horses that could circumnavigate the large lake, knew that this was not true, but to seem politically sensitive in their occupied territory, they said that if Huvsgol is an ocean, it must have 100 rivers running into it.

It was agreed that in two weeks time, Manchu inspectors would gather to count the rivers running into Huvsgol.

The Mongolians gathered the local shamans and Buddhist Lamas, and asked for advice.

The spiritual Lamas and the ancient Shamans who had resided in this region for thousands of years, sat in prayer and meditation.

The night before the inspection date, the heavens opened and a torrential rain fell over the region.

Some say that it had never rained so much in this area, before or since.

On the morning of the inspection, the Manchurian inspectors lowered their heads in defeat when they counted many more than a hundred rivers which had gushed down from the mountain ranges surrounding Huvsgol, blending into this vast body of water.

The "Lake tax" was not imposed in this region and Huvsgol is still called today by Mongolians, "Huvsgol Ocean".

By now, we had developed a routine which we followed when we checked into a ger camp.

First we examined the yurt that was assigned to us, making sure that we had towels and enough wood for the stove.

Then we arranged for the staff to come and start a fire in our ger at a certain time and asked when the hot water would be on, and when can we take a shower.

Then we arranged to meet the cook to discuss our options for food and the time for dinner.

The chef had already spoken to a local woman who runs a meditation retreat in the area, and had asked her for advice about how to make vegetarian food for us.

He made us cucumber soup and traditional Mongolian Buuz (steamed dumplings), filled with vegetables instead of meat.

We were told that there was plenty of hot water for a shower right now, so I took my towel and with hope in my heart, marched over to the shower stalls.

A new bathroom wing was being constructed, and a hole for a new sceptic tank was being dug.

The old showers were tiny cubicles with no water pressure and no hot water.

An attendant who spoke no English, told me to wait while she sent someone to the roof to adjust the heaters and the pump.

She managed to find me a shower stall with a bit of water pressure and gave me a towel and plastic sandals to shower with.

In the middle of my shower, the water ran out.

I heard screaming and running on the roof, and a girl from the kitchen who spoke a smattering of English, opened my shower curtain and told me to finish right now, since the water pump was on fire!

There was a lot of commotion, and two hours later there was enough lukewarm water available for me to go back to the shower and wash the shampoo out of my hair.

Luckily, we were the only guests in this large ger camp which was mostly undergoing a major renovation.

Summertime was the only time that camp owners had to make improvements, and ALL of the ger camps around Mongolia that we saw were in need of some kind of renovations, especially to the bathrooms and shower facilities.

The next day Jules and I went for a hike in the woods surrounding the lake.

We noticed many varieties of wild mushrooms and wildflowers growing in the forest and many, many large herds of yaks, roaming freely in the woods.

It felt a little startling to meet face to face with a huge male yak with his Bull horns.

Some were flaring their nostrils and digging the ground with their hooves as if they were preparing to attack....

We skirted the herds, and tried to avoid walking in their paths.

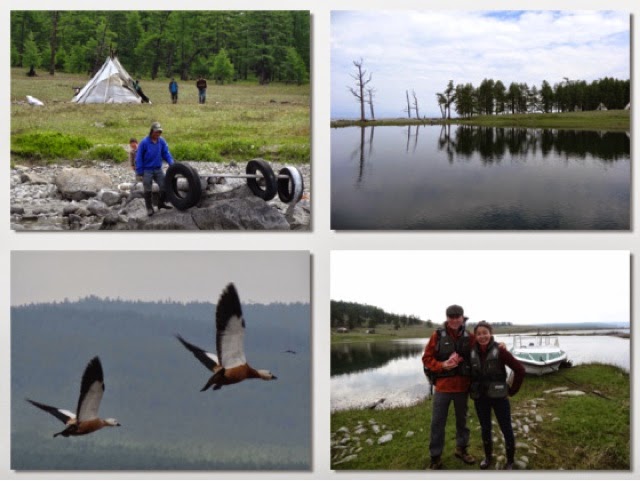

The owner of our ger camp had a small motorboat, and after breakfast, we piled into the boat to go visit a Reindeer nomadic family who comes down every summer from their village up north to camp on the southeastern part of the lake.

They mostly come down to try and earn a living from the tourists.

Some collect herbs and flowers in the Mongolian Taiga where they live, and dry the herbs and make a herbal tea from it, which Is known for its healing properties.

We reached the shores of their camp, and the men came over to help tie up our boat.

This nomadic family belonged to the Tsaatan Dukha tribe.

The Dukha, (also called Duhalar and in Mongolian: Tsaatan) are a small Tuvan Turkic community of reindeer herders living in northern Khövsgöl Aimg Lake.

Only 44 Dukha families remain, totaling somewhere between 200 and 400 people.

They ride, breed, milk, and live off their reindeers.

Traditionally, they are shamans by faith.

They used to eat reindeer meat during the winters, but now the reindeer population, which once numbered in the thousands, has dropped to approximately 600.

The Tsaatan people live in Tipis and not in the more rounded Mongolian Gers.

They used to line their Tipis with Reindeer skins, but now they use only canvas, which needs to be replaced every four to five years.

Much of the Tsaatan's income today comes from tourists who pay to buy their crafts and to ride their domesticated reindeer.

The name "Tsaatan" means "reindeer herder" and "Tsaabug" means a Reindeer.

There were two mangy looking reindeers resting in the shade of a tree, and a large tipi which the family had erected by the shores of the lake.

To ward off the many flies that were attracted to the dung of the reindeers, the family had set up some small dung fires to produce smoke.

We sat in their Tipi and asked many questions.

Traditionally in Mongolian Gers, there are beds and chests, an altar and shelves.

In this Tipi they had no furniture, just some blankets rolled up and a large wooden stove in the middle.

The flour, sugar, milk and other food items they used were arranged on the right side of the Tipi, by the door.

We thought that this was because they only came for the summer months, but the mother told us that this is how they live up north.

They do not have furniture of any kind.

They sleep on a blanket on the floor during winter, with blankets to cover themselves, and in the summertime they sleep outdoors, or inside the tipi with its sides rolled up.

In the cold winters, they pack snow around the sides of the tipi, to prevent the wind from coming through the openings.

The mother had a daughter and two sons.

We were told that her daughter, who was almost a teenager, loves to dress up with nice white dresses and often wears high heels, even though the camp area is muddy and full of animal dung.

The older son was twenty five and was of marrying age.

He shyly mentioned to us that he was looking for a wife.

Jules said that with the upcoming Nadaam festivities, maybe he could find a wife, and the young man smiled and said that that was exactly his plan.

We asked him what would be his criteria for choosing a wife, and he said that his new wife would have to be willing to move up north to live with his family.

We asked him what he would do if she refused, and he said that he would not be able to marry her.

He has no plans to leave his tribe or change his way of life.

The other son was a cute toddler who was called Tugultur which means "A Piano."

I thought it was a strange choice of a name for people who never owned a piano...

The older son had carved some naive patterns into old reindeer horns.

I decided to buy a few of them in order to give them some money.

They were so happy that I purchased three horns at high prices without negotiating, that they offered to let me ride the reindeer.

I said that I did not wish to ride the skinny animal, who seemed so content to lay quietly in the shade.

We drank some salty milk tea made with reindeer milk, and Piano (Tugultur) showed us his toys which included a brightly painted model helicopter. The family also had a solar panel to charge their mobile phone and a motorcycle which they used for transport during the summertime.

They mentioned that they have been coming down here every summer for the last five years, and that nobody else from their tribe made the journey down during the summers, that they all stay up north and care for their animals.

Back in our ger camp, we found that some mischievous prairie dogs had entered our ger under the sidings, and ate some of the candy that we had brought to give to the nomad kids.

We secured everything in a dresser in our ger, and went for a long walk around the lake before dinner.

The next day we drove around the lake to the western side, to visit the harbor village of Hatgal.

We packed a picnic lunch and went for a hike up the mountain, to see the surrounding vistas.

Heavy rain came down and we had to walk hurriedly back down the mountain.

But by the time we reached the village of Hatgal, just a few minutes away, the sun was shining again.

Vendors lined the waterfront, selling traditional crafts, jewelry, smoked fish, canned lake fish, all sort of jams made from local berries, and Taiga tea.

We tasted a local Mongolian dish of Khushuur which are pan fried pockets of dough filled with smoked fish.

They were truly delicious and we took some more to eat later, because our camp chef, despite all his good intentions, just did not have the touch to produce any tasty food.

There were many tourists around, most of them Mongolians who had come for a lake cruise upon the not so seaworthy S.S. Sukhbaatar.

We saw some big Mongolian men hide big bottles of vodka in their dels, as they boarded the ancient sea vessel.

There was loud music and many cries of drunken laughter, coming from people already on board the S.S. Sukhbaatar.

After checking out each of the vendors' tables of treasures, we bought some Taiga herbal tea, some small souvenirs, a beautiful necklace of turquoise stones, and a comb carved from a yak horn.

Since I was already talking about horns - the carved reindeer horns that I had bought from the Tsaatan family and the yak horn comb I bought in Hatgal - Tuya told us a Mongolian folktale that her grandmother had told her, about the camel and the deer.

Once, little Tuya asked her grandmother, "Why do the camels always sit by the water well?"

The grandmother told her that once, a very long time ago, when the earth was still young, all camels had beautiful antlers.

Once a deer approached a camel and asked to try on his horns.

The camel was reluctant to give his antlers to the deer, but the deer promised that he would only borrow the antlers for one night.

He would go to the pond by the well, look at his reflection in the water to see how it suited him, and bring the horns back the very next day.

The camel agreed and gave his antlers to the deer.

The deer put them on and never returned.

And so, to this very day, the camel still sits by the well, hoping one day to get his antlers back.

A Folktale it may be, but there actually is a real, life-size sculpture in the Gobi of a camel with a beautiful set of antlers, to corroborate this ancient Mongolian tale.