Day 58 - The Chūgoku 33 Temple Kannon Pilgrimage, Japan - A Very Exciting Trek to the Cliff Halls of Sanbutsu-ji Temple on Mount Mitoku, and a Bit About Shugendo Mountain Asceticism

Day 58 - The Chūgoku 33 Temple Kannon Pilgrimage, Japan - A Very Exciting Trek to the Cliff Halls of Sanbutsu-ji Temple on Mount Mitoku, and a Bit About Shugendo Mountain Asceticism

We allotted a full day to hike from Misasa Onsen, where we are staying, to Sanbutsuji Temple.

On the map, it did not look like a very long nor a hard hike, but afterwards, I was delighted that we had devoted a full day to this special place.

From our Onsen ryokan, it was only eight kilometers to the entrance of the temple.

But it was a steady and constant climb up the mountain, and it got very steep as we neared the temple.

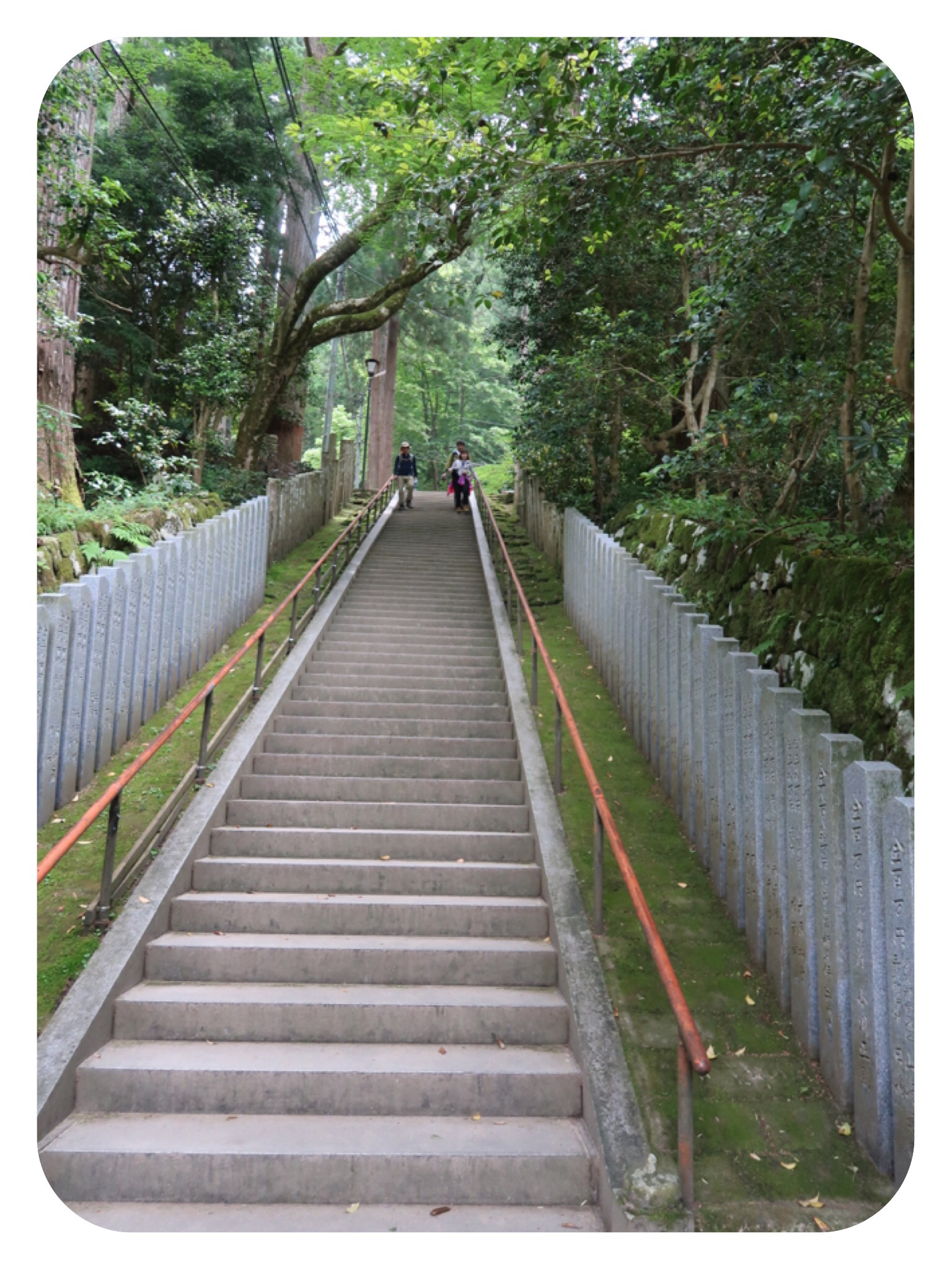

From the entrance to the temple, we climbed up about a hundred stone stairs, to the temple’s first level.

Some of the older stone stairs were worn out by the many feet that have walked on them since the temple was founded 1300 years ago.

A friendly woman collected our entrance fee, and asked if we planned to hike up the mountain to the cave temple of Nageiredo.

We said yes, and she asked to look at the soles of our shoes.

She showed us some samples of black soles with thick sole tread, saying that tennis shoes, sneakers, work shoes, spiked or regular shoes are not allowed.

Hiking poles are also not allowed.

We were not carrying any hiking poles with us anyway.

We showed her the soles of our light trekking shoes, already pretty worn out by walking over 1100 kilometers on our pilgrimage, and she approved them.

To the right of the entrance, we got our pilgrimage book and scroll stamped by a very friendly priest.

He was awed by our nearly full scroll and complimented the Kannon painting I had drawn in the middle of the scroll.

He was a cheerful man and asked us many questions, repeating our answers to another couple from Tokyo who had come to trek to Nageiredo, the highest meditation hall of Sanbutsuji Temple.

There were quite a few people who had come to do the arduous trek that day.

The priest was doubly surprised by the fact that we have been walking the Chūgoku pilgrimage.

He gave us a map of the mountain trek in English.

Since we had already walked for two hours up a very steep road, I thought it would be a good idea if we were to sit and drink something cold in the adjacent temple tea room.

We took off our shoes and were directed to a tatami mat room.

We were seated in front of a pond full of koi in the garden.

We saw the fish jumping out of the water to catch passing flies that had flown too close to the surface of the pond.

I never knew koi could jump like this.

It was a very scenic spot to rest our feet.

We ordered home made ginger-ale, made from sweet ginger root mixed with plain soda.

We also asked for Warabi Mochi, which I LOVE, served with some pear-honey, an iced pear juice, and an order of Mitarashi Dango, mochi balls grilled with pear honey on top.

We stretched out our feet and relaxed, enjoying tremendously the cold drinks and the harmonious zen atmosphere.

When we felt rested, we climbed up to the main hall and chanted the Heart Sutra.

From there, we could see another trekking office, at the entrance to the climb.

Again they checked the soles of our shoes, we paid a small fee, and signed our names and time of entry to a record sheet.

We were given a white sash to wear diagonally across our chests, called a “Wagesa.”

It is worn by pilgrims in Japan when on pilgrimage.

We were asked to remember to return it to the office after we had completed our trek.

Those who did not have hiking shoes were asked to take off their shoes and wear the traditional straw sandals.

We had hiking gloves, which are a MUST on this hike, but for those who did not bring hiking gloves, there were white good-grip gloves to buy for only a dollar.

The forest loomed mysterious in front of us.

We had read nothing about this trek, and had no idea what to expect.

We crossed the Yadoiribashi bridge, painted in red, into a forest of 1000 year old cedar trees.

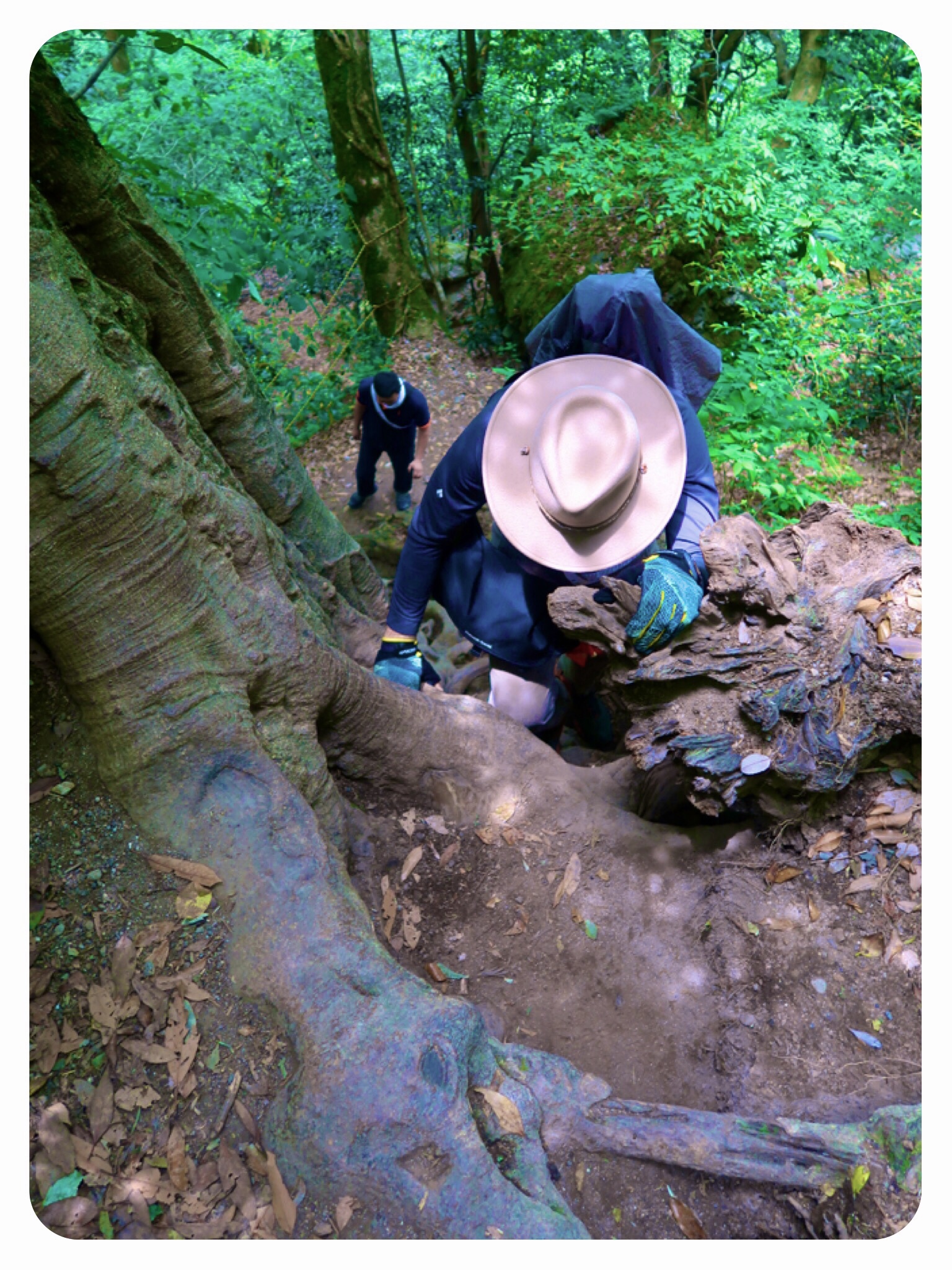

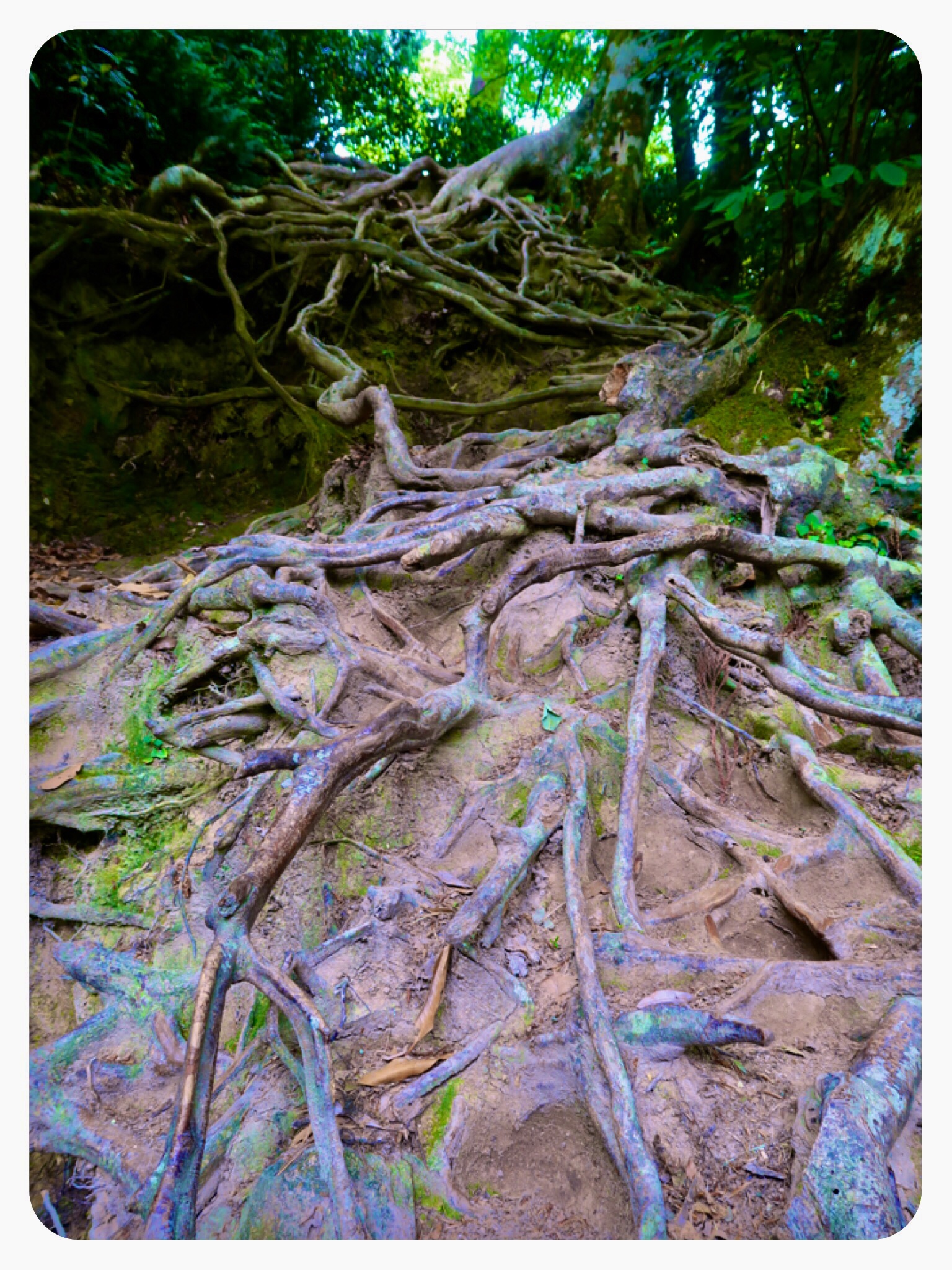

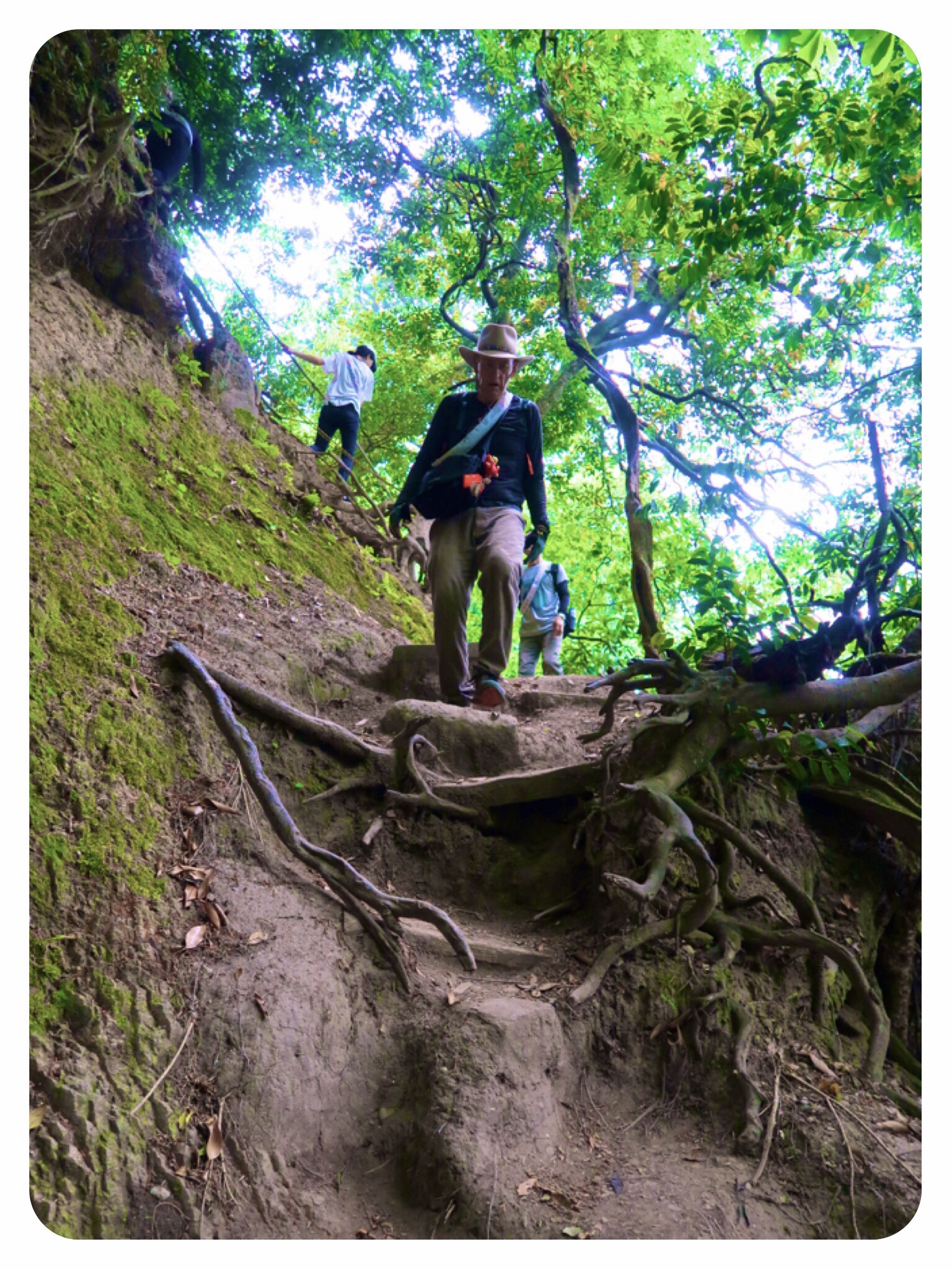

Almost immediately, the path disappeared and what stood before us, was the Kazura-zaka (The Kazura slope).

It was an upward maze of tree roots, that we climbed up like a ladder.

It was vertical, and we had to carefully place our feet on the slippery wood, making sure each root was strong enough before pulling our weight up.

It was like climbing a tricky and uneven ladder.

I already regretted that we did not ask to leave our front bags and scroll at the temple tearoom for safekeeping.

Our front bags dangled dangerously, making our climb difficult.

At the top of the ridge, the path returned, but only for a brief moment. There were more ladders of roots to climb, and each step had to be a conscious move.

You had to place your feet in the grooves of the roots, and find the roots to hold to pull yourself up.

I did not want to even think of the way down, which was on the same path...

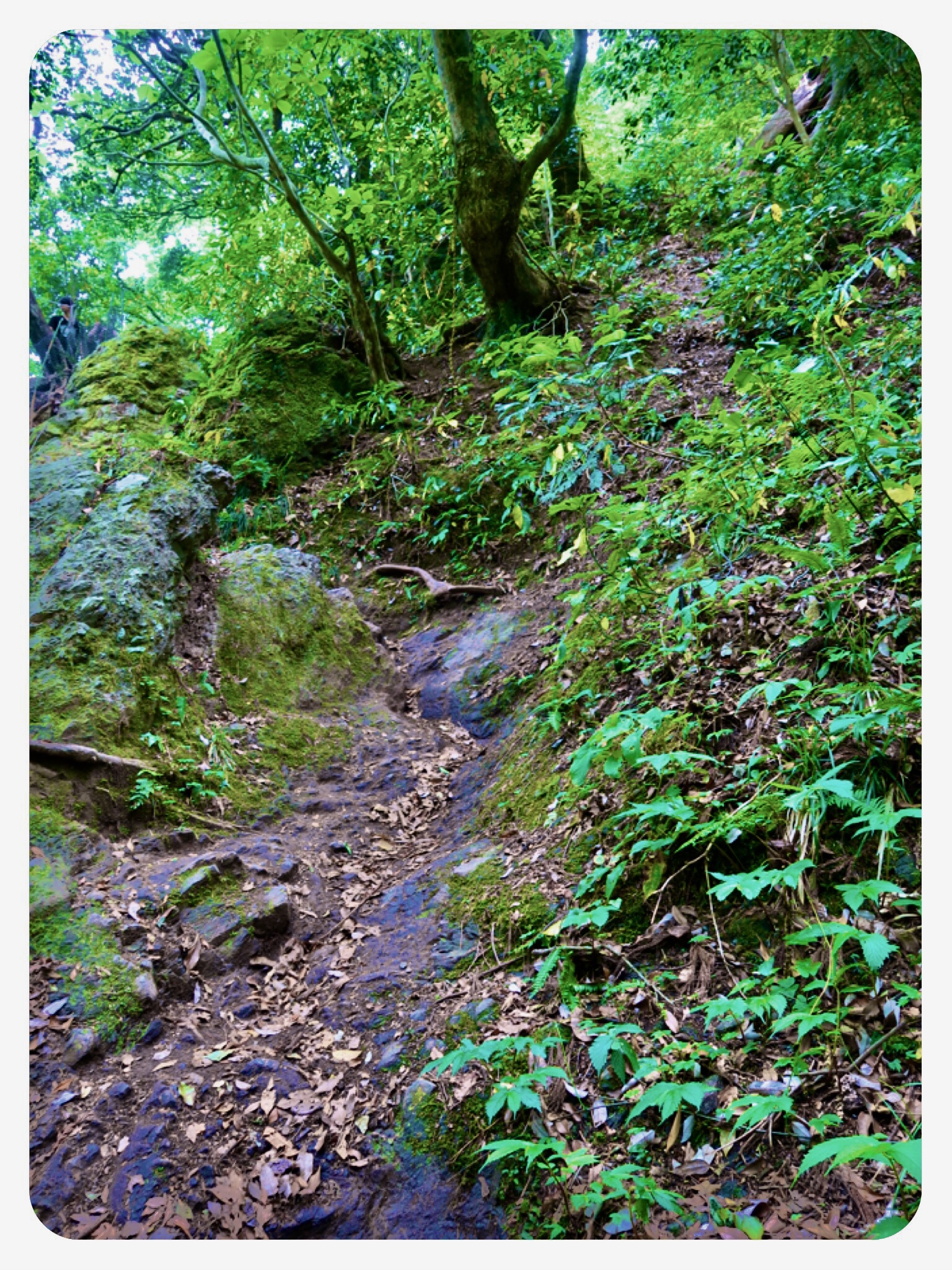

When we finished climbing the path of roots, we climbed up some very steep dry waterfalls, and I realized why this path is not open on very rainy days.

I felt fortunate that the rainy season, normally beginning in June, had not yet started.

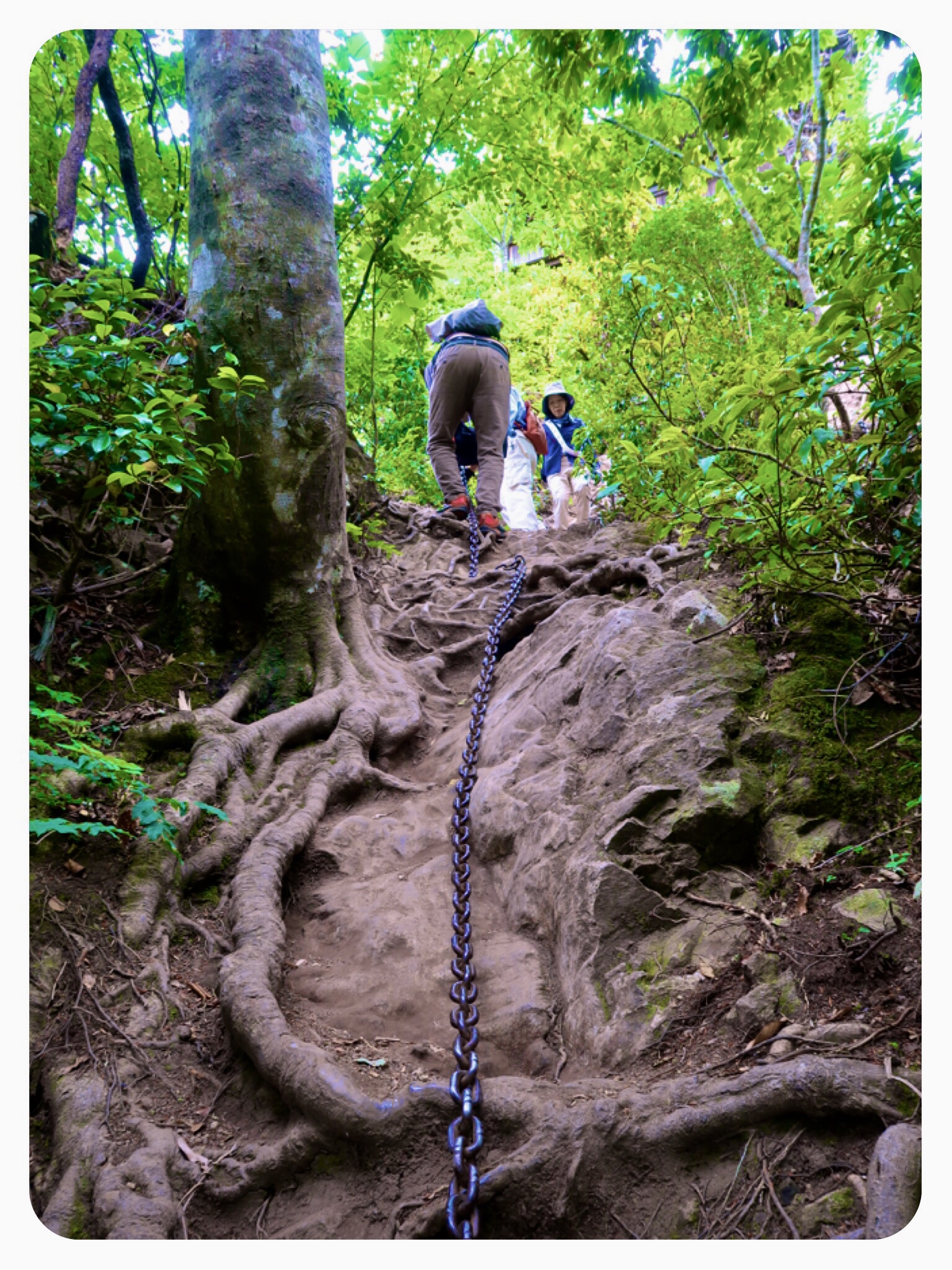

There were steep parts of the path which we climbed with the assistance of well placed ropes, but the hardest part was climbing a vertical rugged stone rock called- the Kusari-Zaka.

This rocky path is so steep, that you have to climb it by holding onto a thick metal chain, with no dents in the cliff rock to place your feet.

I was told that in the olden days, ascetic monks and pilgrims used these metal chains to climb up to the sky meditation halls, since the temple was founded in the year 706.

On top of this very steep mountain, rocky and dense with vegetation, it seemed so hard to understand how they were able to build any temple buildings.

My mind was boggled by how they were able to carry any material up those cliffs.

We were barley managing carrying our bags, which I regretted not leaving behind...

But there are a few temple meditation halls built in these most remote and precipitous locations, on the way to Nageiredo - the highest meditation hall of Sanbutsuji Temple.

In one sky perched hall, we took off our shoes and walked around the narrow wraparound deck.

I felt a fear of heights just standing there, suspended in midair above the vast abyss below me.

There were no guardrails, nothing to protect from a clumsy move, or a momentarily mindless person from falling into the rocky jungle below, hundreds of feet straight down...

How did they build these meditation halls in the sky.....

How did they survive the snowy winters here, when access was nearly impossible and food so scarce....

It is all a wonderful and mystical part of history, unfortunately not told widely nor often enough.

But I will tell it here, because my own fascination with Shugendo started about ten years ago, when we hiked another pilgrimage in Japan.

It is called the Dewa Sanzan, a trek and a climb to three holy mountains, in Yamagata prefecture.

It all started with an amazing Master called En-No-Gyōja.

En-no-Gyōja was an ascetic, a Natural healer, a mystic Truth seeker who is well known in Japan as being the founder of the Shugendo branch of Buddhism.

Shugendo is an ancient Japanese mountain ascetic tradition, inspired mainly by esoteric Buddhism, Taoism, and local shamanistic Shinto.

The name, “Shugendo,” means: “The Way To Gain Spiritual Powers Through Discipline and Training.”

Shugendo is very much alive and thriving in Japan, although not as faithfully practiced by disciples as it once was.

In the past, practitioners did incredible feats of endurance as a means of transcending the physical body and the belief in the solid physical world.

Training included such tasks as long pilgrimages, very restricted diets, overcoming all fears by facing them in rigorous conditions, and endurance of the most extreme elements, like great snow and heat.

Evidence of Shugendo's most extreme tests of physical endurance can be seen here in this sky top mountain where ascetics lived and meditated, and along the Dewa Sanzan pilgrimage, which we did ten years ago.

Part of Dewa Sanzan's appeal for the Yamabushi is its remoteness.

Devout Shugendo followers are called yamabushi, meaning “one who prostrates on a mountain,” or “mountain priest.”

These were once hermits who lived in the mountains and underwent intense training.

Yamabushi would sit under cold strong waterfalls as a way to practice endurance and transcendent meditation.

Heavy snowfall makes travel in the mountains difficult during the winter months.

The three mountains we hiked were:

Haguru-San

Yudono-San

Gas-San

The pilgrimage is a long mountain trek representing “BIRTH” (Haguro-san), “DEATH” (Gas-san) and “REBIRTH” (Yudono-san).

The mountains are usually visited in that order.

Along this pilgrimage route, we saw the Self-mummified bodies of a few Yamabushi monks who had passed on by choice and raised the vibrations of their bodies so high, that they still had not decayed many hundreds of years later.

Unlike the Egyptian methods, these Yamabushi did not use any wrappings.

Some mummified themselves sitting up.

The practice of self-mummification is staggering.

The Yamabushi monks endured three 1000 day periods of dietary restriction, intense physical activity and meditation.

For the first thousand days, they ate only mountain vegetables, while continuing to practice the physical hardships of Shugendo training.

For the second 1000 day period, the diet was restricted even further, to just bark and roots.

The monks who succeeded in stepping out of their physical bodies into their spiritual light energy bodies, preserved their physical bodies as mummies through this extreme diet modification and meditation.

Although the practice is now banned in Japan, these self-mummified monks are considered living Buddhas for their achievement.

Today, Shugendo is primarily associated with the Tendai and Shingon sects of Buddhism.

In Yamagata, we stayed in a guesthouse belonging to a Yamabushi man, who took us to walk on a huge burning hot rock barefoot.

At that time, about ten years ago, foreigners were only allowed this honor by private invitation from a Yamabushi member of the Shugendo sect.

The term Yamabushi has now come to describe any follower of Shugendo, even those who do not practice mountain asceticism.

About the legendary mystic En no Gyoja, not much is known for certain. It is well known that he was wrongfully banished by the Japanese imperial court in the year 699 because of fears of his supernatural powers.

Standing on top of the sky mountain he established here in Mount Mitokusan, it is easy to believe that he did achieve Sidi Spiritual Powers.

Here it is said that En-No-Gyōja used his supernatural powers to throw Nageiredo hall onto the cliff face where it still stands today.

It was this magical act that gave the hall its current name, “Nageiredo,” which means “Thrown-on temple”.

According to some tales, he flew to Mount Fuji every night to train and to worship.

Today the halls and the temple are under the protection of the Prefectural Preservation of Cultural Property of Japan.

It is said that the temple name "Sanbutsu-ji" (3 Buddhas) of Mt. Mitoku, was derived from the three revered Buddhas enshrined here in the year 849 by Jikaku Daishi Ennin.

The three Buddhas are the “Shaka Nyorai,” “Amida Nyorai” and “Dainichi Nyorai”.

The trek up this 900-meter tall Mt. Mitoku, was tiring for our already tired bodies.

The sheer precipice and the rugged climb left us tired, and we still wanted to walk all the way back to Misasa Onsen, where we were staying for another night, instead of taking the hourly bus back.

We stopped again at the temple tearoom, but this time to have lunch.

We ordered the vegetable curry lunch set, which included a curry with bamboo, carrots and mountain vegetables served with rice, a salad and a cold glass of ginger ale.

We rested as much as we could, and then walked another two hours back to Misasa Onsen.

The lady who runs our guesthouse agreed to do our laundry for free.

She must’ve sensed our tiredness when we asked her if she knew if there was a coin laundry in town.

After resting, bathing and soaking in the hot springs, we dressed in the summer kimonos the inn gave us, and waddled around the stone paths of the village in our borrowed wooden geta sandals, to find a place to eat dinner.

Most places were closed or booked for a private party.

We finally found a small place open and plumped ourselves in front of the TV, at one of their Okonomiyaki grill tables.

They served us a delicious Okonomiyaki, a shrimp sushi roll and edamame.

It was a simple but very tasty meal, a good end for a wonderful, exciting and a little tiring day.

Wishing you a most wonderful day/night,

Tali

Daily Stats:

Steps: 26,904 steps

Distance Walked: 20 Kilometers

Active Walking: 5 hours

Total Time: 9 hours

Total distance walked on the pilgrimage so far: 1159.5 Kilometers

Temples Visited: Temple #31, Sanbutsuji Temple (Mitokusan Nageiredo) 三仏寺 in Misasa

Accommodation: Mejisou Onsen ryokan, in Misasa Onsen.

A well kept and well run inn with spacious Japanese style rooms, a small hot springs bath, and fast internet, in a famous and charming spa town.

Offers meals by prior arrangement (we took only breakfast).