Day 16 - Walking The Nakasendō, Japan - Learning About the Kofun Period, The Jomon Pit Houses, The Birthplace Of Soba, and Entering The Kiso Valley

Day 16 - Walking The Nakasendō, Japan - Learning About the Kofun Period, The Jomon Pit Houses, The Birthplace Of Soba, and Entering The Kiso Valley

From Shiojiri, we started to walk southwest towards the Kiso Valley.

The area is surrounded by mountains, and the Nakasendo path follows the fast moving Kiso River, in a valley that zigzags between mountains.

We had already been walking for nearly two kilometers when I realized that we were walking in the opposite direction, back towards Tokyo.

We turned back and started walking in the right direction.

Jules took it in good spirits, but I, being the Navigator, felt bad for making the kind of mistake that required us to retrace our steps.

Soon, we left the small town and walked through fields filled with apple groves and grape vines.

In a small agricultural area, a farmer stopped his truck and told me to go visit the nearby archeological and historical sites.

There were earth mounds from the Kofun era, and very interesting round thatched houses, from the Jomon period.

The Jomon lived in hearth homes.

At the very beginning of the Jomon era (10,000-8,000 BC), the Jomon were hunter-gatherers and lived in caves or rock shelters, as people in the Paleolithic era did.

Very soon, however, the Jomon people learned to build and to live in pit dwellings. And for nearly 10,000 years, pit dwellings continued to be the basic kind of home for people living in Japan.

There were two types of basic dwellings during the Jomon period:

1) Pit-type dwelling – which consisted of a shallow pit with an earthen floor covered by a thatched roof.

2) Circular dwelling – a round floor was made from dried clay or stones, and covered with a circular roof.

The pit houses we visited were larger, with thatched roofs supported by sturdy posts set deep into the ground.

The thick thatched roofs reached all the way to the floor, and created a very intriguing design effect.

Pit houses in those early days were often built so that the floors were sunk into the subterranean earth level so that the earth’s natural warmth made for more comfortable homes.

Floors were often a half meter below ground level, and were usually just dirt or earthen floors tamped down hard.

In the very beginning, Jomon homes were mere circular huts, like the recreated ones we saw today.

The houses had fireplaces inside, allowing for indoor cooking and helping to smoke away insects and keep the occupants warm.

The earth mound we saw was from the Kofun era, which lasted from AD 250 - 538.

The Kofun period is marked by the use of burial mounds erected for the elite, varying in size and shape from round or square mounds to hundred meter long keyhole shaped ones.

The Kofun burial mounds and their remains have been found all over Japan.

The most interesting ones are the ones shaped like a keyhole, that can be only seen as a keyhole when seen from above.

It is a fascinating design as in those times, airplanes were not yet invented and it brings to mind why they created such massive keyhole-shaped mounds, several meters wide by a few hundred meters long.

It is believed that the religion of Shinto emerged during the Kofun period.

The word, “SHINTO,” translates to “THE WAY OF THE GODS.”

The practice of Shinto focuses on ritual performance to maintain a proper lifestyle, as well as a connection to the gods, or Kami, as they are called in Japanese.

The Kami are gods or spirits who embody natural powers such as the sea, sun, mountains, forests, rivers, lakes, creeks, wind, storms, moon, rocks, water, stones, as well as powerful energy forces like compassion, abundance, wealth, harvest, Heaven, war or the underworld.

Although most Kami were associated with nature, some are powerful people, spiritual masters and emperor or warriors.

At first, no special temples or shrines were created to worship the Kami, and any prayers or worship could be done by anyone, either in the open or in a sacred space like forests, by anyone who cared to do so.

It was only later that Kami started to be worshipped in temples and shrines by clan chiefs and priests.

These Shinto shrines are usually marked by a Tori gate.

The Kami were not believed to be living in the shrine, temple, or sacred spot that was dedicated to them, but rather it is believed that they visited these locations and occupy a statue or figure that depicted them.

From there, we walked through buckwheat fields that were already harvested and not yet replanted.

In the station town of Motoyama Juku, we stopped to eat at an unassuming Soba restaurant that is called, “The Birthplace Of Soba.”

Nearby, there is a monument to the birthplace of Soba (soba is noodles made from buckwheat).

It shows that soba was born in the Kiso Valley.

It is believed that in the 14th century, soba was a portable food that was able to be carried up to the holy monks who lived and practiced on the isolated summit of Mt. Ontake.

Soba later became a local specialty of the Kaida Highlands, and later spread all over Japan.

The Soba restaurant called Motoyama Sobanosato, offers soba that is seeded, harvested and milled all from the surrounding fields, and handmade by local women.

You can see the pure white buckwheat flower fields if you visit the area in the autumn.

The restaurant was not too busy, and we sat at a comfortable table, took off our shoes and backpacks and sat to enjoy a soba meal.

First we got hot tea and parsley pickles, as well as pink Radish pickles and Nigauri (bitter gourd).

Jules got a tempura Soba, served hot in a soup with a tempura vegetables and a shrimp cake on the top.

I had the Soba tasting set, which included Zalu Soba with a soy dipping sauce, grated daikon, scallions and wasabi.

A buckwheat and mushroom salad, a soup which contained Sobagaki, a soba dumpling-shaped ball made of buckwheat and served in a tasty broth, and a Soba ball for dessert, which was very wholesome and tasty.

We were not very hungry when we entered, but it was good that we ate, because beside eating in such a unique place, the birthplace of Soba in all of Japan, we also did not pass by any other place to eat after that, for many kilometers.

The walk today was long, much longer than we had intended.

I was hoping to pace our days a little slower and less long, but when you add sightseeing to a pilgrimage, the mileage adds up.

My feet hurt after kilometer twenty, but we still had a long way to go to get to Narai Juku, where our Minshuku (guesthouse) for the night was located.

We stopped along the way at a truck stop, and, sitting among truck drivers who all were drinking multiple huge bottles of beer, we ate some ice cream and tea and rested our feet.

The town of Kisohirasawa is well known for its production of lacquerware.

The town is stunning, with a wide Main Street and many well maintained period shops and houses.

We walked through it, amazed at the beauty around us.

I noticed that when I am in awe of the beauty around me, walking on my tired feet gets much easier.

Narai Juku is a beautiful old town with most houses still preserved from the Edo Period.

It feels like you have just stepped into an ancient town.

Our Minshuku Shimada, In the middle of Narai, is an old guesthouse with a very friendly owner.

We met two other couples, walking the Kiso Road by using a self guided tour service, a couple from New Zealand and a couple from Philadelphia.

We all ate our dinner in the main dinning room, sitting on the floor in front of the low tables, eating the good food the owner had put in front of us.

The Minshuku has some large tatami guest rooms, but we booked it at the last minute, so the best rooms were already taken.

We got a small but comfortable bedroom with two well worn futon mats and buckwheat pillows.

But, as we are pilgrims, comfort is not a big part of a long foot pilgrimage.

A pilgrim is happy for a warm place to rest, where the kind people offer her a hot shower, a place to lay her head, a hot fresh meal and a place to refresh our energies.

This was such a place.

Run by a friendly and sweet woman who chatted with us in Japanese, admired our long task, and told us that she has only met Japanese people who have walked the whole pilgrimage.

“The Japanese pilgrims I have met, would have never taken a detour to see Matsumoto or do any other sightseeing outside of the Nakasendo path... but I guess you were curious...,” she said with a sympathetic smile.

With love and blessings,

Tali and Jules

Day 16 - Stats:

Total walking time 8.5 hours

Active walking time 7.2 hours

Total steps: 41,787 steps

Daily Kilometers: 30.5 Kilometers

Total Kilometers walked up to date: 375 Kilometers

Accommodation: Minshuku Shimada In Narai- a historic, authentic guesthouse with tatami rooms, shared toilet and bathroom, a friendly family that serves good dinner and breakfast.

Total elevation climbed 1,858 meters

Total descent 1,643 meters

Maximum Altitude reached 943 meters

Station Towns visited in Nagano Prefecture:

30. Shiojiri-shuku (Shiojiri) (also part of the Shio no Michi)

31. Seba-juku (Shiojiri)

32. Motoyama-juku (Shiojiri)

33. Niekawa-juku (Shiojiri)

34. Narai-juku (Shiojiri)

A little about the Station towns visited:

Seba-Juku - Station #31

The area was named "Seba," which means "Washing a horse," when a soldier of Minamoto no Yoshinaka, washed his master's horse in the waters here.

Seba-juku was originally established in 1614, along with Shiojiri-juku and Motoyama-juku, in order to accommodate the travelers on the Nakasendō's route.

Motoyama-juku - Station #32

Motoyama became a post town in 1614, when the Nakasendō's route was changed.

It became known throughout the country for its soba noodles.

Niekawa-juku - Station #33

Niekawa was originally written as (niekawa, "warm river") because there were onsen in the area, which made the river warm.

However, the kanji were eventually changed to the ones used today.

Originally built in the Tenbun period (1532-1555), it was the first of 11 resting spots along the Kisoji, which stretched to modern-day Nakatsugawa, Gifu Prefecture.

It also marked the dividing point between the lands of Owari Han clan and Matsumoto han clan.

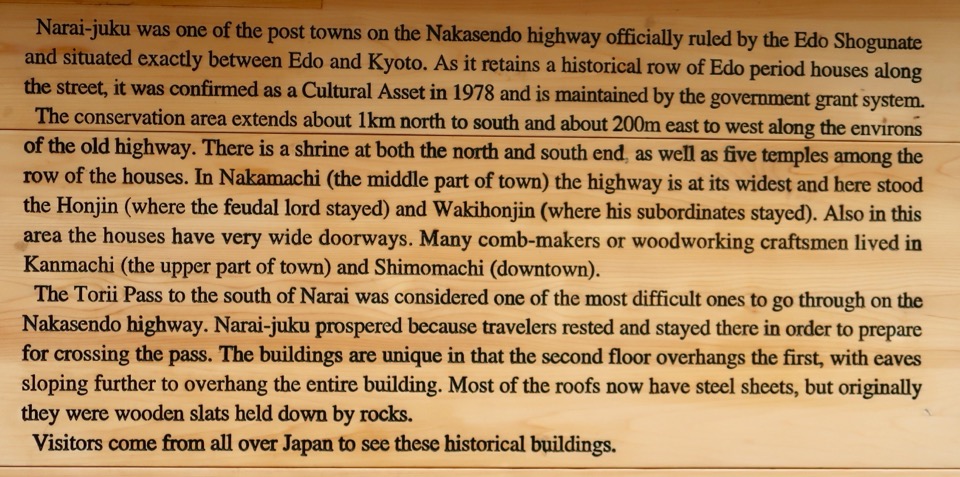

Narai-juku - Station #34th of the sixty-nine stations of the Nakasendō, as well as the second of eleven stations along the Kisoji.

Narai-juku had the highest elevation of all the spots along the Kisoji.

Because of all the visitors going through the Torii Pass (Torii Tōge), Narai flourished as a post town and was referred to as "Narai of 1,000 buildings."

It has since become one of Japan's Nationally Designated Architectural Preservation Sites, so the buildings have been kept much like they originally were in the Edo period.

There are a few small workshops still making beautiful wooden combs, a traditional craft in Narai.